John Simon, who died yesterday at age 94, had one of the two or three most unremittingly independent voices in criticism. Advertisers and editors probably tried to control his signature vitriol or his devastating judgments, but it's obvious they failed.

The most striking thing about his body of work (from Acid Test in 1964 and Movies into Film in 1971 to Something to Declare in 1984 and The Sheep from the Goats in 1987) is its autonomy and singularity (in fact, his 1975 anthology of long theater essays—on Peer Gynt, on The Wild Duck—is called Singularities). Aside from Edmund Wilson, there was nobody else in American letters quite like Simon, a critic by innate temperament who combined academic formalism with a journalist’s impulse for influencing the collective taste of educated readers (many of whom undoubtedly didn’t much care for movies anyway). Dwight Macdonald could cut the spindly legs out from under mass culture with equal ease and spirit, but Macdonald had a jokey, teasing quality which Simon completely lacked. Macdonald hated garbage as vehemently as Simon (read Macdonald’s takedown of the Hollywood biblical epics in the 1969 On Movies), but he didn’t give you the impression, despite all his masscult and midcult categorizing, that he himself was an inaccessible, displaced alien of superiority, passing judgment on a hopeless demotic culture, as Simon always did. Maybe that difference was the innate extension of Simon’s Old World pedantry (he was the sort to correct you on your use of polymath when you really meant polyhistor).

An ace polemicist, Simon was praised and reviled just about equally throughout his career. One anecdote should suffice: In 1969–70, Simon was a recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism (voted on by the Cornell, Princeton, and Yale English department faculty), and that same year the New York Drama Critics’ Circle voted to keep him out of that august body.

Simon in interviews encouraged his notoriety as a harsh, nearly unpleasable critic with a mandarin disdain for pop and ersatz in the arts. I always thought this was unfortunate because that reputation ossified around him like a crust until it obscured his clarion voice in print. He was almost always described as the “Count Dracula of film critics” or “the skunk at the party” (not to mention the endless agitated charges of sexism, homophobia, and misanthropy), and his funny descriptions of the physiognomies and various protuberances of Liza Minnelli and Barbra Streisand invariably appeared, way up top, in virtually everything ever written about him. It was his fault: his frequent apologia—that film was a gesamptkunstwerk in which every element, designed or not, played an important part in the viewer’s experience—was never very convincing. He just loved skewering ugliness, whether of a costume, a speaking voice, a set backdrop, or a receding chin.

Compared with his contemporaries—other critics in his league—Simon used a prose style that was indistinguishable from the opinions themselves. The singular force of his judgment was his style, whereas his colleagues—Macdonald, Vernon Young, Robert Bentley, Stanley Kauffmann, and so on—had more idiosyncratic styles with a rhetorical lightness that shaped their opinions. When he wasn’t firing on all cylinders, Simon was a starch-collared, stentorian writer who was inclined to announce that he was about to be witty right before being so (although he was often genuinely so—“As Marge, Frances McDormand verges on the cutesy but manages in the nick of time to pull herself back from the verge”). His other recurring weakness was the stringing out of lengthy tropes until you felt as if you were watching money compound in the bank (“A similar visual fakery has the gifted but often excessive cinematographer Allen Daviau bedizen the movie with every sort of unearned visual opulence as further aid in audience-besotting”). Typically, he lines up his perfectly poised, well-structured phrases in a nagging, anal-retentive way that saps his point of some of its energy: “The trouble with JFK is that whereas it solicits a second seeing to unscramble it, it does not offer enough aesthetic compensation to warrant the effort of reimmersion.” Think of how much pithier Rossini was about Wagner, saying the same thing.

Simon’s voice felt far more authoritative—and inquisitive—when he was writing about European movies and plays. He seemed more at home with European sensibilities. In the introduction to Something to Declare, his anthology of foreign film reviews, Simon admitted that he rejected that view, but it was always true. The art films of early Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, Ozu, Troell, and the like were his true purview. In writing about them, he delved more deeply and described more acutely than he did with American studio films, whose messiness and market exigencies probably occupied only a fourth of Simon’s analytic ability and his interest. (He almost never discussed seriously or at length a movie’s financial battles or its box office.) It’s his writing on European movies—on their explorations of sexual politics, their intimacy and reflection, their avant garde rhetoric, and their literary symbolism—that will stay in the memory of Simon’s close readers. Let the rest of the world keep their Count Dracula.

Monday, November 25, 2019

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

American Realism

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) apotheosizes the American gangster picture genre. It subsumes all other classic gangster pictures, from Underworld (1929), The Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) to The Roaring Twenties (1939), White Heat (1949), and The Killing (1956). But The Godfather Part II (1974) does what no other gangster picture—even The Godfather—ever did. With the relentless, excoriating scalpel of nineteenth-century novels and the plays of Chekhov—the laboratory of literary realism—Part II flayed the layers of superficiality (those earlier movies’ stock in trade) off the underlying complexity of Michael Corleone (Al Pacino). As a study of despoiled idealism and the effects of social organization on the members of a powerful tribal family, Part II analyzes Michael as profoundly as any of the main characters are analyzed in the novels of Balzac, Howells, Wharton, or Eliot.

The Godfather was perhaps the single greatest example of epic romanticism in the New American Cinema. The tidal-wave sweep of the story and the gallery of characters are rich and expertly acted but framed in melodramatic terms scaled to the spectacle of the film. Michael, his siblings, his father (Marlon Brando as the old Corleone, the family man as institution), his family’s caporegime and legal retainers, and the maze of partners and “soldiers” are realistic types, but types (and stock characters) nonetheless: the proud patriarch; the thoughtful, independent younger son; the hothead older son (James Caan); and the array of lackeys, bodyguards, and operations men. These characters are vibrant examples of literary and cinematic creations, but they don’t really evolve or reveal new shadings over the course of the movie, and we aren’t shown their doubts or twisted self-hatred. The movie succeeds as brutal enchantment—as a charismatic cast of characters in a sophisticatedly stylized melodrama. There’s something Dickensian about the dramatic parade of character types passing across the screen. The movie’s visual richness, framing, and montage (which speeds up and cross-cuts so suspensefully you may be reminded of the competing and ultimately colliding stories in the climax of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance) are pitched to the dimensions of the theater. (More than just about any other movie of its era, The Godfather deserves to be seen on the big screen.)

The Godfather Part II is equally a triumph of personal filmmaking, but its analytical mind is far deeper. It goes beyond the romanticism of its predecessor into a new vein of realism in American movies. Part II puts Michael, Fredo Corleone (John Cazale) and Hyman Roth (Lee Strasberg)—and perhaps even the Frank Pentangeli of Michael V. Gazzo as well as Robert De Niro’s beautifully realized Vito Corleone—under closer scrutiny (as if the camera were a magnifying glass), demonstrating a complexity of character analysis you almost never saw in genre movies until this one. The treatment of these characters fills them out with the complications and completeness of real human beings. Coppola replaces much of the mythic resonance and symbolic significance of the first Godfather film with a new naturalism and verisimilitude. Michael’s and Fredo’s motives and moods alternately lurch forward and fold back on themselves in unpredictable yet totally believable ways, their emotions bubbling to the surface one minute and being sublimated the next (Pacino excels at abrupt flareups of anger—you’re shocked but fully convinced of his frustrations). These characters are anything but stock and they aren’t even symbolic here. They are far too complex for facile symbolism or the creaking mechanics of traditional storytelling devices. Like us, they change their minds and grapple with the messy self-doubts and sordidness of life. The complexity of Part II is that these men aren’t mouthpieces for ideas or dramatic “techniques” or tools for advancing the plot; like the great characters in novels, they seem to have lives outside the text—lives, in fact, that are far richer than even Coppola’s operatic vision can capture.

As an epic generational saga and a portrait of the moral ambiguity at the heart of finance and business (possibly a metaphor of the movie business itself), The Godfather Part II is peerless. It casts an influential shadow over just about everything after it, including John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday (1980), Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (1984), and Martin Scorsese’s rather facile Goodfellas (1990). Even Quentin Tarentino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Brian De Palma’s nervy, erotic thriller Carlito’s Way (1993) pay homage to Part II (and have to grapple with new styles to escape its massive imprint). Of what other postwar American film can you say that even major works look like tinfoil up against it?

The Godfather was perhaps the single greatest example of epic romanticism in the New American Cinema. The tidal-wave sweep of the story and the gallery of characters are rich and expertly acted but framed in melodramatic terms scaled to the spectacle of the film. Michael, his siblings, his father (Marlon Brando as the old Corleone, the family man as institution), his family’s caporegime and legal retainers, and the maze of partners and “soldiers” are realistic types, but types (and stock characters) nonetheless: the proud patriarch; the thoughtful, independent younger son; the hothead older son (James Caan); and the array of lackeys, bodyguards, and operations men. These characters are vibrant examples of literary and cinematic creations, but they don’t really evolve or reveal new shadings over the course of the movie, and we aren’t shown their doubts or twisted self-hatred. The movie succeeds as brutal enchantment—as a charismatic cast of characters in a sophisticatedly stylized melodrama. There’s something Dickensian about the dramatic parade of character types passing across the screen. The movie’s visual richness, framing, and montage (which speeds up and cross-cuts so suspensefully you may be reminded of the competing and ultimately colliding stories in the climax of D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance) are pitched to the dimensions of the theater. (More than just about any other movie of its era, The Godfather deserves to be seen on the big screen.)

|

| Real men. Al Pacino |

As an epic generational saga and a portrait of the moral ambiguity at the heart of finance and business (possibly a metaphor of the movie business itself), The Godfather Part II is peerless. It casts an influential shadow over just about everything after it, including John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday (1980), Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (1984), and Martin Scorsese’s rather facile Goodfellas (1990). Even Quentin Tarentino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Brian De Palma’s nervy, erotic thriller Carlito’s Way (1993) pay homage to Part II (and have to grapple with new styles to escape its massive imprint). Of what other postwar American film can you say that even major works look like tinfoil up against it?

Monday, November 11, 2019

Shlock from Shintoho

I’ve now seen two movies by the Japanese director Nobuo Nakagawa, whose reputation, thanks to Criterion and Turner Classic Movies, has reached ridiculous overinflation. I usually love films that are so ambitious dramatically or visually that you can appreciate their barmy edges; in the very best of these films, such as The Thief of Bagdad (1924) or Napoléon (1927), it’s like watching Jacob wrestle with God’s angel. (The director busts his hip bone, too.)

In some movies made by brilliant eccentrics such as Raoul Walsh or Abel Gance, enchanted ideas come spilling out, overflowing the ordinary constraints of production design, camerawork, and narrative. Ideas are executed with an almost religious fervor, an impresario’s spirit—as if the director were driven to express something so deep within him that it was as if he needed to make the grandest summing up of all, the Alpha and the Omega of cinematic statements. Because the plots are incoherent or the themes jumbled or the point of view ambivalent or self-contradictory (as it sometimes is in Fritz Lang or Alfred Hitchcock or G. W. Pabst), audiences may be befuddled about details or flow, but they watch these movies in a state of heightened excitement. Their senses are alert to possibilities they didn’t even know existed, and the experience can be overwhelming.

But Nakagawa’s movies aren’t barmy and creative in this way; they’re just freakishly melodramatic and puerile, with screams and shrieks filling the soundtrack at random. (Remember those “Sounds of Halloween Haunted Houses” records you bought as a kid?) They’re low-budget bores—thirty minutes in, you’ve had it with the penny-effects and the inanity. You feel as if you’ve been dragging toddlers around the neighborhood on Halloween, enduring garage “funhouses” and stick witches from those converted costume stores. His two most esteemed movies, Jigoku (1960) and Ghost Story of Yotsuya (1959), both made at Shintoho, have none of the elegance, brilliance, or genuine terror of Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1965) or Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (The Black Cat) (1968). Jigoku, particularly, is a medieval morality play overlaid with giallo shlock (with none of Mario Bava’s skill with camera angles or basic narrative ploys), ketchup blood from Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations (the kind that appears to have been thickened with cornstarch until it resembles a gelatinous blob of pomegranate juice), and a script that Ed Wood probably turned down. It’s a testament to Nakagawa’s inexpertise, I suppose, that he generates tedium even out of such promising ingredients.

|

| Gelatinous blob. Jigoku. |

But Nakagawa’s movies aren’t barmy and creative in this way; they’re just freakishly melodramatic and puerile, with screams and shrieks filling the soundtrack at random. (Remember those “Sounds of Halloween Haunted Houses” records you bought as a kid?) They’re low-budget bores—thirty minutes in, you’ve had it with the penny-effects and the inanity. You feel as if you’ve been dragging toddlers around the neighborhood on Halloween, enduring garage “funhouses” and stick witches from those converted costume stores. His two most esteemed movies, Jigoku (1960) and Ghost Story of Yotsuya (1959), both made at Shintoho, have none of the elegance, brilliance, or genuine terror of Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1965) or Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (The Black Cat) (1968). Jigoku, particularly, is a medieval morality play overlaid with giallo shlock (with none of Mario Bava’s skill with camera angles or basic narrative ploys), ketchup blood from Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations (the kind that appears to have been thickened with cornstarch until it resembles a gelatinous blob of pomegranate juice), and a script that Ed Wood probably turned down. It’s a testament to Nakagawa’s inexpertise, I suppose, that he generates tedium even out of such promising ingredients.

Friday, August 30, 2019

The Elements

No wonder that primitive people worshipped nature as a god: the harsher that nature becomes, the more grandeur and beauty it has. In explosive bursts of power, it subdues us, and we exalt it in return. The people in Robert Flaherty’s elemental Man of Aran (1934) live by the skin of their teeth—they can barely manage to keep themselves fed—but they celebrate their proximity to the very force that threatens them daily.

In movies such as Nanook of the North (1922), The Pottery Maker (1925), and Moana (1926), Flaherty, who started as a still-photographer, developed a style that has been called “narrative documentary,” “docufiction,” and “ethnofiction.” Whatever one calls it, its filmic impact is undeniable. Certain aspects are fictionalized or anachronistic, such as the basking shark hunt in Man of Aran, but audiences respond rapturously to Flaherty’s alchemy—the way he combines anthropological accuracy with the aesthetic drive of storytelling and characterization. Before Nanook, Flaherty had traveled to Hudson Bay with an early movie camera to film the Inuit people. But he rejected the results—the “filmed nature” approach without any artistic shaping or organization, which anthropologists might consider “true” documentary—referring to them as pointless and boring.

In Man of Aran, Flaherty scripted characters in naturalistic settings—the tiny hovels and villages in the Aran Islands off the storm-battered west coast of Ireland—and then cast local fishermen and their wives and children in those parts. These non-actors have craggy, leathery faces and gnarled hands; they’re the weather-beaten salt of the earth of primitive myths. No part of their lives is ornamental; everything seems destined either to signify their scrappy religious faith or to increase their chances for survival. Even their homes—huts or shacks—show virtually no sign of impracticality; these people, engaged in epic battles against nature, have no time for tea, as they say.

Man of Aran is marvelous cinema. Few other movies or styles combine realism and spirituality with this much primitivist poetry.

|

| The Atlantic Ocean as a venerated threat. |

|

| Trying to save the wooden-hulled craft. |

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

The Razor’s Edge

|

| Shenanigans. Elliot Gould, Tom Skerritt, Donald Sutherland |

|

| The Last Supper. |

The miracle of MASH is that it so successfully combines the taboo breaching of gallows humor—laughing at suffering to stay sane—with the naturalistic coarseness of low comedy: the movie balances bone saws and foul mouths, and spills off the screen in torrents. Although Korea is the ostensible setting, you know that the movie is really showing the madness of Vietnam, and telling America that it’s possible to do good work and sustain your sanity and humanity amid the senselessness of bloodshed and strangling bureaucracy. The effect is restorative, a work of humanism. MASH is a Rabelaisian black comedy, and one of the most sensible American movie satires ever.

Elders

|

| Filial devotion. Teiji Takahashi and Kinuyo Tanaka |

The film is uncannily beautiful, a moral work of art, and a transcendent vision of filial love. It’s also one of the greatest movie allegories of mortality: how the all-too-briefness of life exacerbates our miseries and poisons our attempts at kindness, which is life’s insuperable tragedy. As Orin, the old woman whose children are all too ready to abandon her to her terrible fate, Kinuyo Tanaka is the apotheosis of the Shakespearean clown: her wizened face framed by a dirty-blonde bob, she’s a miraculous mix of pitiable silliness and heartrending despair. Teiji Takahashi brings understated ambivalence to his role as Tatsuhei, Orin’s one decent offspring, and the two together give the rare movie impression of actual blood relations between actors.

The paradox is plain in Narayama (as it is in its thematic kin, King Lear): because of our brief, bookended lives, if we’re sane, we tell humane stories. This particular story was adapted from a 1956 novella Narayama bushiko (Ballad of Narayama) by Shichiro Fukazawa, and was remade in 1983 by Shohei Imamura in a grittier, naturalistic style. But there is no greater use of realism than in the final scene of Kinoshita’s version.

Out of Italy

The celebrated partnership of Vittorio De Sica, an actor who became one of Italy’s—and the West’s—most revered directors, and Cesare Zavattini, a screenwriter and film theorist, was inaugurated in the movies with the luminous The Children Are Watching Us in 1944, although the two knew each other for more than a decade prior. Together, their collaborations of Italian neorealism were more mystical and allegorical than the harsher social portraits of corruption and decay in the work of other Italian neorealists like Luchino Visconti and Roberto Rossellini. The De Sica-Zavattini films are smaller-scale studies in frailty and innocence; instead of making Grand Statements about politics and society, they paint individuals in unselfconscious but lyrical strokes—prose poetry character studies. If, years after viewing, we’ve forgotten the scenes of wartorn Rome and its political infighting in Rossellini, we probably still remember the disillusioned faces in De Sica.

Zavattini’s realism is an homage to the nineteenth century Russian novelists, particularly Turgenev and Tolstoy. (Jean Renoir paid tribute to the Russian and French realists in much the same way.) De Sica, a great director, uses actors’ faces and classic narrative conventions like linearity and situational irony to tell stories of the bereft—losers, dreamers, and children enduring the cold hopelessness of life on the skids. He hits his mark, too. The emotional impact of these movies wells up like a rising tide, evenly and surely. In the final scene of The Children Are Watching Us, the camera fixes on the back of the abandoned child as he trudges away, and the indictment of all squabbling, selfish, vain adults is complete.

|

| Scenes from childhood. Luciano De Ambrosis |

The De Sica-Zavattini collaboration produced about twenty films, including the hallowed masterpieces Shoeshine (1946), Bicycle Thieves (1948), Miracle in Milan (1951), and Umberto D. (1952). The Children Are Watching Us isn’t quite one of the masterpieces, but its incandescence and Petrarchan sweetness can’t be shaken off easily. It points the way to the fables of childhood in Truffaut, the Taviani brothers, and Shunji Iwai.

Friday, June 7, 2019

Headlines

|

| News ink. Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell |

By the middle of the 1940s, the era of carefree screwball stories about newsmen, wisecracking society dames, and daffy heiresses was largely played out, and His Girl Friday was thus not only perhaps the greatest but also one of the last of its kind. American audiences turned their attention to events in Europe, and found there wasn’t much left to laugh at. Movies got propagandistic and returned to serious, “noble” homefront themes, as in Mrs. Miniver (1942), Since You Went Away (1944), and The White Cliffs of Dover (1944). The war sapped comedic energies and soured the public on its old urge to satirize its sacred cows.

Staying Alive

|

| Wolves. Nobuko Otowa, Kei Sato, and Jitsuko Yoshimura |

Pretensions

“[It] possesses a distinctly playful atmosphere and carefree cadences.” [The Criterion Collection catalogue]

No, it most certainly does not. All These Women (1964) is a limp, desultory farce. Apparently, Ingmar Bergman, one of the most sophisticated spiritual artists in film—the equal of the great, dour existentialists in the other arts—decided to write and direct this disoriented, enervated gimmick in order to make extra money. Bergman and Sven Nykvist developed a pastel color palette for the movie, which gives the nonsense onscreen far more visual depth than it merits.

|

| The red and the black. |

I don’t believe I’ve ever seen another movie by a master filmmaker that’s both stylishly pompous and hamfisted. I certainly never expected to see a pie thrown in someone’s face in a Bergman film. But if this knucklehead production had happened on the stage, I think people would have thrown tomatoes.

Show Biz

|

| Dollar for dollar. Ginger Rogers |

Thursday, June 6, 2019

The Greatness of Audacity

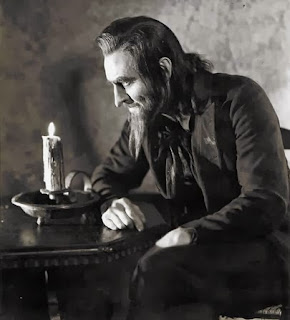

|

| Mesmerizer. Jack Barrymore |

John Barrymore (Broadway’s Orson Welles) in Svengali (1931) unpacks theatrical traditions and his own sly, self-referential archness into a variety of grand gestures—the sing-song accents, interrogative upturns, and squeaky upper registers of the Eastern European Jew; the static postures and bearing of the angular nobles in the Eisenstein historical epics (Barrymore is made up to resemble Nikolay Cherkasov in Ivan the Terrible); and the tortured self-doubts and sadism of the Shakespearean villains. Barrymore is so audacious that all these styles blend seamlessly—he gets to the essence of the art of acting: creating a character that is both lifelike and larger than life. When his great death scene occurs, you expect him to spring uncannily back to life. And the special effects in the mesmerism scenes have sensual heat: Svengali’s eyes glow like molten metal.

Screwball

The loose, romantic playfulness of Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) is lifted from screwball comedy of the 1930s. This laid-back romp gives Woody Allen and Diane Keaton an opportunity to be Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Bringing Up Baby (1938), Ray Milland and Jean Arthur in Easy Living (1937), and Claudette Colbert and Don Ameche in Midnight (1939), and it has the most sustained tempo of any of Allen’s movies of that time. (Alice, from 1989, is a lovely flight fantasy for the first hour, but gets bogged down in marital melodrama in the last half—its whimsical romance dissipates into sodden confusion and leaves moviegoers bummed out.)

This movie’s central conceit is the romantic gambol of the old screwballs: the frisky girl (often played by Carole Lombard, Irene Dunne, or Jean Arthur) is in the mood for an adventure, while the shy, straightlaced guy wants no part of it, but nervously follows her anyway because she’s such a babe—Henry Fonda was the quintessential lovestruck nerd in The Lady Eve (1941). Here, it’s Keaton, back to form after The Lemon Sisters (1990) and the atrocious Father of the Bride (1991), leading a constantly protesting Woody Allen around with a ring in his nose, sneaking into people’s apartments to scout for clues.

Like those earlier screwballs, Manhattan Murder Mystery has its classic sequence: Allen, Keaton, and friends (Alan Alda and Anjelica Huston), a quartet of intrepid amateur detectives, concoct a plan to blackmail the suspected killer by playing prerecorded messages on a cassette tape over the phone to simulate an actual conversation. Naturally, the tapes get all jumbled and the “conversation” hits a snag and ends up sounding like gobbledygook. It plays better than it sounds—it’s a sidesplitter. The last scene, too, is delightful—a climactic shootout amid a maze of mirrors and projection screens (it was a mistake, however, for Allen to project The Lady from Shanghai on one of the screens to underscore the idea).

Manhattan Murder Mystery is a plush, snug recliner: you can settle yourself in and have a good time watching Keaton and Allen ham it up and banter inventively—they make marvelous company—while old movie references fly back and forth. Things are close to the spirit of the madcap ’30s here—a lot closer in spirit than Peter Bogdanovich’s nagging, largely witless What’s Up, Doc? (1972) or even several of the 1980s Allen comedies. In Manhattan Murder Mystery, Woody Allen got his groove back.

|

| Daffy detectives. Diane Keaton and Woody Allen |

Like those earlier screwballs, Manhattan Murder Mystery has its classic sequence: Allen, Keaton, and friends (Alan Alda and Anjelica Huston), a quartet of intrepid amateur detectives, concoct a plan to blackmail the suspected killer by playing prerecorded messages on a cassette tape over the phone to simulate an actual conversation. Naturally, the tapes get all jumbled and the “conversation” hits a snag and ends up sounding like gobbledygook. It plays better than it sounds—it’s a sidesplitter. The last scene, too, is delightful—a climactic shootout amid a maze of mirrors and projection screens (it was a mistake, however, for Allen to project The Lady from Shanghai on one of the screens to underscore the idea).

Manhattan Murder Mystery is a plush, snug recliner: you can settle yourself in and have a good time watching Keaton and Allen ham it up and banter inventively—they make marvelous company—while old movie references fly back and forth. Things are close to the spirit of the madcap ’30s here—a lot closer in spirit than Peter Bogdanovich’s nagging, largely witless What’s Up, Doc? (1972) or even several of the 1980s Allen comedies. In Manhattan Murder Mystery, Woody Allen got his groove back.

Blubber

What made Rex Harrison want to be in Dr. Doolittle (1967)? Was he strapped for cash? Did he screen Barabbas (1961) or Fantastic Voyage (1966) or The Vikings (1958) and have an overwhelming urge to be on a set with Richard Fleischer? Was he hankering to deliver dialogue written by the insipid Leslie Bricusse, or sing-speak his mind-numbing songs, with their canned Broadway blandness, about the virtues of vegetarianism? Did Harrison think that his style of drawing-room urbanity would be complemented by the obnoxious Anthony Newley, whose acting career was distinguished by broad yuk-yuks and refrigerated ham?

Did Harrison think that audiences in the late sixties—Film Generation college audiences who were getting turned on to European directors and experimental styles—wanted gut-busting dances and stale, phoned-in stupidity from a bygone age of movie musical crap, an anachronistic big-studio production that’s too long for kids to sit still through and too asinine for normal adults to stand?

Maybe Harrison had a more practical motive. Did 20th Century-Fox offer to put his grandchildren through college?

This monstrosity of a musical achieves a dubious distinction: even at a time of awful musicals from the major studios, it’s completely devoid of merit. Not a single scene, not a single song, not even a single sentence has any charm or appeal. It’s in another universe entirely from the sometimes brilliant and reliably entertaining Freed Unit musicals from MGM—Singin’ in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), It’s Always Fair Weather (1955), and a few of those dazzling Judy Garland musicals.

It’s hardly surprising that this waste of celluloid has absolutely nothing in common with the craftsmanship and energy of Arthur Freed. What is surprising is that contemporaneous movie musicals—blubbery movies at the time like Camelot (1967), The Happiest Millionaire (1967), Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), Hello, Dolly! (1969), Paint Your Wagon (1969), and Sweet Charity (1969), nearly all of which were ruinous disasters that ultimately sank the big Hollywood studios financially—have moments with some appeal: a passable number here, a clever bit of comedy there. Dr. Doolittle stands apart even in such a crowd; it may be the worst stinking musical of its time.

Every response you’re likely to have, scene by scene, song by song, seems inadvertent. Watching the posh, sexless Harrison in his silk opera hat sing a love song to a seal doesn’t exactly generate tender feelings in you; you’re more likely to react with revulsion. For hapless viewers, including the kids whom parents probably dragged to this thing in droves in 1967, this beached whale of a movie is human–animal abuse.

Did Harrison think that audiences in the late sixties—Film Generation college audiences who were getting turned on to European directors and experimental styles—wanted gut-busting dances and stale, phoned-in stupidity from a bygone age of movie musical crap, an anachronistic big-studio production that’s too long for kids to sit still through and too asinine for normal adults to stand?

Maybe Harrison had a more practical motive. Did 20th Century-Fox offer to put his grandchildren through college?

|

| Seal abuse. Rex Harrison |

It’s hardly surprising that this waste of celluloid has absolutely nothing in common with the craftsmanship and energy of Arthur Freed. What is surprising is that contemporaneous movie musicals—blubbery movies at the time like Camelot (1967), The Happiest Millionaire (1967), Thoroughly Modern Millie (1967), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), Hello, Dolly! (1969), Paint Your Wagon (1969), and Sweet Charity (1969), nearly all of which were ruinous disasters that ultimately sank the big Hollywood studios financially—have moments with some appeal: a passable number here, a clever bit of comedy there. Dr. Doolittle stands apart even in such a crowd; it may be the worst stinking musical of its time.

Every response you’re likely to have, scene by scene, song by song, seems inadvertent. Watching the posh, sexless Harrison in his silk opera hat sing a love song to a seal doesn’t exactly generate tender feelings in you; you’re more likely to react with revulsion. For hapless viewers, including the kids whom parents probably dragged to this thing in droves in 1967, this beached whale of a movie is human–animal abuse.

Moviegoing

|

| Generation gap. Al Pacino and Marlon Brando |

But whatever it was, it was evanescent and got swallowed up, again, in crummy commercialism and emotional banality—crass and impersonal junk like Flashdance (1983), Footloose (1984), and Top Gun (1986): TV on steroids. My heart sank just thinking about how the deluge of teen crud in the 1980s was pushing out what little bits of quality appeared, almost by magic, every so often in American commercial film.

Thirty years later, American movies are largely a crass, obnoxious art of hyperactive cutting and visceral sensations—computer dinosaurs and what-all—with the mental dimensions of arcade games and theme park thrill rides. Movies are designed for ultra-high dpi resolutions and nanosecond refresh rates. Those who find the current experience of today’s blockbusters breathtaking must be having the time of their lives.

|

| Transformation scene. Bette Davis |

Before HDTV and home theater systems, people were better off going to the theater to see not only those movies with impressive visual dimensions (Citizen Kane, 1900, La Ronde) but also movies whose intended effects relied on communal audience involvement—sidesplitting comedies and melodramas like Now, Voyager (1942) seemed stronger when people around you laughed or gasped as you did when you first saw the slimmed-down, elegant Charlotte Vale (Bette Davis) in spectator pumps and hat on the ship’s gangway. When we opt to stay home to watch, I think we forgo the communalism of an audience of strangers who are reacting just like us. In many cases, moviegoing really is a shared experience—like a neighborhood’s banding together in the face of adversity.

Not so much these days, but there were times when I went to see an old movie (Genevieve, for example, or a Jack Barrymore comedy) at a revival theater to experience the audience reaction to my favorite parts. I wanted to see these strangers respond like me, because their responses made them seem, momentarily at least, closer than actual friends. After a good movie—an immersive, great narrative experience like The Godfather Part II (1974), for example—I loved walking back up the aisle in the dim light with the rest of the audience, and I just knew that everyone was dazedly thinking the same thing, and the god of movies had bestowed a rare gift.

A Capricious Masterpiece

Jean Renoir’s La Règle du jeu (1939) was voted the third greatest film of all time by an international group of critics for a 1962 Sight and Sound poll, and the fourth greatest film of all time by a 2012 panel of critics and scholars brought together by the British Film Institute. This fabled masterpiece is widely regarded as the greatest French film by a master French director, and decade after decade hangs on to its hallowed place at the summit of world cinema.

Apart from its standing with the experts, La Règle du jeu is in just about every movie lover’s Top Ten. It’s as rich an experience as you are likely to have in a theater; you’ll never see the movie’s neoclassical sources of continental theater performed with as much shattering brilliance. Renoir and his team (which included Henri Cartier-Bresson as an assistant) infuse centuries of high comic tradition into a Modernist farce that only appears as if it were spinning out of control. In fact, it’s a completely controlled tragicomedy in which chance, or fate, is the prime mover.

Just about every social or cultural anchor—love, honor, class, even classical distinctions between literary genres—is dismantled in La Règle. The title is doubly ironic: the social classes abided by their rules in prewar Europe, love had its rules, comedy and tragedy had their rules. Renoir smashes these rules into pieces. La Règle in 1939 points the way to the absurdist strain in Modernism. The animal hunt is a shocking, profound visualization of the slaughter during the Great War and the slaughter to come—warfare on land (the rabbits) and in the air (the birds). (When Germany marched into Czechoslovakia in March 1939, several of Renoir’s technicians left the filming to join the army.)

The idea of the disintegration of class distinctions, of class relationships teeming with infidelity and jealousy, had been dramatized in Musset (whose Les Caprices de Marianne Renoir used as a springboard), Beaumarchais, and Molière. In La Règle, ignobility is society’s great leveler (the way cats all seem to be the same color at night), much as you find it in Enlightenment theater traditions. But the movie pounces on the modern: civilization itself becomes a witches’ sabbath in which sentiment is juxtaposed with raunchy sex chases, heroes (like the hapless aviator) are turned into victims of mischief, and the intricate organizing impulse of society itself crumbles into a mayhem of poaching (both animal and sexual). In earlier French literature, immoral and moral were binary opposites, but in La Règle it’s the revelrous commingling of the immoral with the amoral that drives our experience. That’s what makes the movie so absolutely modern, and so sustaining. Like the Shakespearean comedies, this Renoir masterpiece lets us peer more deeply into our social and sexual selves.

|

| The hunt. Mila Parely |

Just about every social or cultural anchor—love, honor, class, even classical distinctions between literary genres—is dismantled in La Règle. The title is doubly ironic: the social classes abided by their rules in prewar Europe, love had its rules, comedy and tragedy had their rules. Renoir smashes these rules into pieces. La Règle in 1939 points the way to the absurdist strain in Modernism. The animal hunt is a shocking, profound visualization of the slaughter during the Great War and the slaughter to come—warfare on land (the rabbits) and in the air (the birds). (When Germany marched into Czechoslovakia in March 1939, several of Renoir’s technicians left the filming to join the army.)

The idea of the disintegration of class distinctions, of class relationships teeming with infidelity and jealousy, had been dramatized in Musset (whose Les Caprices de Marianne Renoir used as a springboard), Beaumarchais, and Molière. In La Règle, ignobility is society’s great leveler (the way cats all seem to be the same color at night), much as you find it in Enlightenment theater traditions. But the movie pounces on the modern: civilization itself becomes a witches’ sabbath in which sentiment is juxtaposed with raunchy sex chases, heroes (like the hapless aviator) are turned into victims of mischief, and the intricate organizing impulse of society itself crumbles into a mayhem of poaching (both animal and sexual). In earlier French literature, immoral and moral were binary opposites, but in La Règle it’s the revelrous commingling of the immoral with the amoral that drives our experience. That’s what makes the movie so absolutely modern, and so sustaining. Like the Shakespearean comedies, this Renoir masterpiece lets us peer more deeply into our social and sexual selves.

The Boom

The Great Gatsby (2013) is a brashly kinetic adaptation of a literary landmark. Filled with flaws of taste, it nonetheless has a primal power, balancing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Americana lyricism with a eurotrash sensibility. Baz Luhrmann’s direction goes beyond realism—beyond hyperrealism, even—into a garishly ornate romanticism, a jewel-encrusted, stylized vision of the 1920s as distant from historical reality as a fairy tale. Luhrmann makes the florid hysteria of Ken Russell (The Devils, The Music Lovers, Savage Messiah) seem tranquil by comparison. But Fitzgerald’s poignant, homespun longing elevates this movie above Russell’s emotional barrenness.

Except for Leonardo DiCaprio (a clotheshorse who looks a little pudgy around the jowls), the cast is much too tightly controlled by the iron-clamp production to be able to create human beings with believable idiosyncrasies—the kind of visual or verbal toss-offs or imperfections that allow a performance to breathe, to acquire deeper and sometimes darker dimensions as a movie unfolds. The actors, including the appealing Tobey Maguire as Nick, Carey Mulligan as an unmagical Daisy, Joel Edgerton (whose face is as stony as Gary Cooper) as the cruelly pragmatic Tom, and Elizabeth Debicki as Jordan, are unfortunately all swamped; they’re doll-like props in Luhrmann’s explosive tableaus. New York is designed like a steampunk variation of Jules Verne, and the Art Deco mansions look like steely, cartoonish Studio 54s. This is the sort of production design that blurs the line between movie dreams and nightmares. (You might want to bring aspirin for after the movie.)

DiCaprio is able to do more than adopt Jazz Age poses against these flaming tableaus. He impressively navigates the megatechnology and whiz-bang camera (which swoops over Manhattan like a Star Wars spacecraft), and he steals a great many scenes (except perhaps those with his gorgeous Duesenberg, whose shimmering yellow coat of paint mirrors Gatsby’s tailored suit). Nearly a century after it was published, Gatsby’s self-made man stills pulls people in deeply enough so that their emotions are profoundly resonant. In post-Horatio-Alger America, Gatsby was serendipitously mentored, financed, and launched. Fitzgerald’s golden tale has exerted its power through four or five film versions (and another several TV adaptations), always washing away most of the production flaws. American audiences are attached to Fitzgerald at the hip—fixated on the boulevard-of-broken-dreams theme of corrupted hope, which is the green light of our collective movie past.

|

| Boulevard of broken dreams. |

DiCaprio is able to do more than adopt Jazz Age poses against these flaming tableaus. He impressively navigates the megatechnology and whiz-bang camera (which swoops over Manhattan like a Star Wars spacecraft), and he steals a great many scenes (except perhaps those with his gorgeous Duesenberg, whose shimmering yellow coat of paint mirrors Gatsby’s tailored suit). Nearly a century after it was published, Gatsby’s self-made man stills pulls people in deeply enough so that their emotions are profoundly resonant. In post-Horatio-Alger America, Gatsby was serendipitously mentored, financed, and launched. Fitzgerald’s golden tale has exerted its power through four or five film versions (and another several TV adaptations), always washing away most of the production flaws. American audiences are attached to Fitzgerald at the hip—fixated on the boulevard-of-broken-dreams theme of corrupted hope, which is the green light of our collective movie past.

Fast Food

The Bank Job (2008) is a cheap buzz, neither likable nor memorable. This heist thriller fulfills the most superficial purpose of movies: you get a slight kick out of the twists and folds, and then easily walk away from it. There’s practically nothing in the way of humor, let alone wit, and the plot lurches around in fits: the silly business with the head burglar and his estranged wife comes out of nowhere, trying to generate poignancy, but it’s a no go. A neurasthenic action film is a bummer for moviegoers.

That subplot wraps up in the lamest scene in the movie—only a child or a dunderhead would fall for it. Not a single performance stands out, either as especially skilled—or as notably bad, for that matter. In fact, nothing stands out at all. One of the few responses I can remember having was thinking how much the crime boss looked like David Suchet; when I looked up the character online and found that he was David Suchet, I nodded and said, “Hmm” to myself. Everything goes down quickly, without eliciting love or disgust—other than the disgust you might feel at having yet another nondescript action flick shoved your way. This movie isn’t embraced or repelled, it’s consumed.

That subplot wraps up in the lamest scene in the movie—only a child or a dunderhead would fall for it. Not a single performance stands out, either as especially skilled—or as notably bad, for that matter. In fact, nothing stands out at all. One of the few responses I can remember having was thinking how much the crime boss looked like David Suchet; when I looked up the character online and found that he was David Suchet, I nodded and said, “Hmm” to myself. Everything goes down quickly, without eliciting love or disgust—other than the disgust you might feel at having yet another nondescript action flick shoved your way. This movie isn’t embraced or repelled, it’s consumed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)