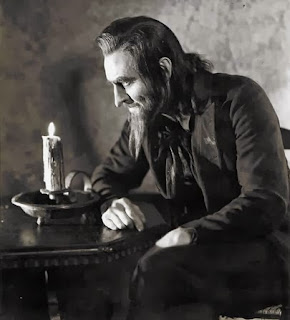

In The Black Cat (1934), a perverse dark-and-stormy-night creeper, the Poverty Row legend Edgar G. Ulmer sets up his camera and lights his sets

as well as any A-string director. He builds mood through perspective and angle. Ulmer also has a supremely literary bent — you can see that his conceptual inventiveness comes from a mind that knows and loves books. He’s whack the way old ghost stories are whack. In movies like The Black Cat, The Strange Woman (1946), and Detour (1945), Ulmer isn’t a terribly good action director; neither was Josef von Sternberg. Sternberg kept his camera in motion but almost never pulled off a compelling action scene with his actors. Ulmer worked as a set designer for Max Reinhardt in the theater and apprenticed with F. W. Murnau on Sunrise (1927). His true strength was setting, not action. These directors excelled in static intensity. When Ulmer attempts to move the story in The Black Cat forward with simple action — as he does when David Manners is conked out twice, and we wait for him to come to so that he can rescue Jacqueline Wells, but he never does, or when Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi physically tussle — the effect is abrupt or incoherent, a real dud. But Ulmer is superb at creating that sense of campy dread that everyone enjoys in The Black Cat, quite like the fun of seeing the work of James Whale in The Old, Dark House (1932) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). When Lugosi reaches over to fondle the blonde hair on the sleeping heroine, it’s a peerless kinky moment.

|

| Good kitty. Jacqueline Wells |